Parents’ advice benefits African American youth – when they seek support

Adolescence is a critical time for developing social skills and youth often navigate difficult peer experiences. Parents can help their children by giving advice on how to deal with challenges, but it matters whether youth want support or not. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign looks at the impact of parental advice and youth support seeking in African American families.

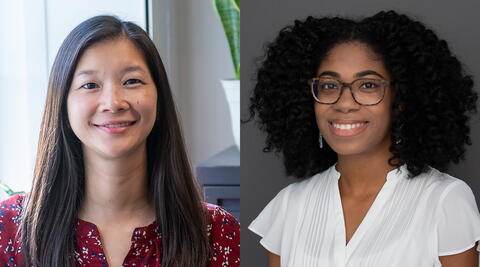

“A lot of existing research was conducted with predominantly White samples, and we wanted to learn more about whether similar experiences exist for Black families as well. We focused on the types of advice parents give their kids when it comes to challenging peer situations, and how the advice affects the youth’s social cognitive skills one year later,” said lead author Virnaliz Jimenez, a doctoral student in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, part of the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at Illinois.

The study included a sample of predominantly rural, low-income African American families in the Southeastern U.S. Children were on average 12 years old and transitioning to or already in middle school. More than 80% of the families had an annual household income of less than $50,000.

Youth and their parents completed questionnaires at two time points one year apart. Youth read two peer situation scenarios – inviting peers to their birthday party and joining an after-school club – then answered questions that assessed their social appraisal and self-efficacy beliefs.

“Social appraisal is basically how you interpret an ambiguous situation or the intentions of others. Self-efficacy is how much confidence you have in your ability to deal with the situation,” Jimenez said.

Parents were presented with three peer challenge scenarios addressing peer exclusion, anxiety about meeting new peers, and trouble making friends, and asked to write down suggestions they might give to their child in these situations.

“We focused on cognitive restructuring advice, which is about helping the child understand or view the situation in a less negative or non-threatening way. If there is a peer conflict, parents might suggest that their child think about best case scenario as opposed to worst case scenario, for example, considering that someone was just having a bad day rather than intentionally trying to be mean,” said co-author Kelly Tu, associate professor in HDFS. Parent responses ranged from none or vague to specific and detailed.

Overall, the researchers found no direct effects of parental advice on either of the social cognitive measures. However, when youth sought their parents’ support, elaborate cognitive restructuring advice was associated with more positive social appraisals.

“Many of these kids were transitioning to middle school, and they may have a lot of anxiety about how they’ll fit in and how they will interact with their peers. Constructive advice from parents can be very important in helping them think about the situation in a less threatening way. But if the kids aren’t interested or don’t want to hear it, the advice is less likely to matter for changing their social appraisals,” Jimenez noted.

However, Tu said that, unlike some studies, they didn’t find adverse consequences of unsolicited advice. Yet, when children were looking for advice but not getting it, they had lower positive social appraisals regarding peer interactions; that is, they were more likely to interpret peer challenges in a negative light.

The researchers say these findings underscore that parents should listen to their kids when considering how much advice to provide.

“Reciprocity is important, so parents can ask their kids how they can support them in a given situation. If the youth wants advice, it should be detailed and specific, helping the child reframe a situation and be able to interact with peers in a more positive way,” Jimenez stated.

Practitioners working with families can equip parents with tools that enhance their parenting strategies, such as providing examples of what elaborate, cognitive restructuring advice looks like and how to help kids reframe challenging peer situations towards more positive outcomes.

The research broadens the understanding of parent-child interactions that haven’t typically been studied in this population, Tu said.

“While there is a larger body of research on parenting in Black families around racial ethnic socialization and discrimination, we wanted to expand this work by examining how Black families navigate different types of stressful peer situations. Being able to showcase the range of parenting advice Black parents are giving can help to break down negative stereotypes of low-income Black families,” she concluded.

The paper, “Social Cognitive Skills in African American Youth: Parental Cognitive Restructuring and Youth Support Seeking,” is published in Social Development [DOI:10.1111/sode.12794].

This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (BCS 0921271) awarded to Stephen A. Erath, a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (F31HD069152) awarded to Kelly M. Tu, and a grant from the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station (ALA010-047) awarded to Gregory S. Pettit and Stephen A. Erath. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.