Lost or leading the way? Rare birds may signal shifting migration routes

On a 2009 hike in the Huachuca Mountains of southeastern Arizona, a group of birders heard an otherworldly, ethereal bird song floating, flute-like, through the canyon. The hikers identified the singer as a brown-backed solitaire, recognizing immediately that the bird was very far from home. The brown-backed solitaire spends its life in the mountain forests of Mexico and Central America — what was it doing in Arizona?

“We had no idea what it was, but we knew it didn’t belong,” said Benjamin Van Doren, who was hiking with a birding youth group that day. “I had recordings of some thrush species from Mexico. When I played the first one, which happened to be a brown-backed solitaire, it was a perfect match.”

Then a teenager, Van Doren helped document the first accepted occurrence of the species in the United States, earning him his first scholarly publication. Now, Van Doren is an ornithologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and he’s still interested in vagrants: birds that show up outside their normal range or migratory route.

He’s not alone. Most birders are excited to see and chase vagrants, especially during migration season. They represent an unusual occurrence and offer a chance to observe a species outside of its usual range, sometimes dramatically far from home.

And, for ornithologists, the presence of vagrants begs all sorts of ecological and evolutionary questions: Where did they originate? Why have these individuals deviated from their “pre-programmed” migration route? Are they really evolutionary dead-ends, as scientists have long believed? After all, if an individual flies off course and doesn’t make it back to its breeding grounds, it may never reproduce.

Inspired by his early experience with the brown-backed solitaire — and many vagrant sightings since — Van Doren worked with colleagues at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Point Blue Conservation Science to answer some longstanding questions. They recently published their work in the journal Ornithology.

“Vagrants are very hard to study and understand because you never know where or when they're going to show up. It's typically very unpredictable,” said Van Doren, an assistant professor in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, part of the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at Illinois. “But there are some places that seem to be magnets for rare birds. One of those is the Farallon Islands off the coast of California. For whatever reason, migratory birds that should have been on the other side of the continent show up there every year.”

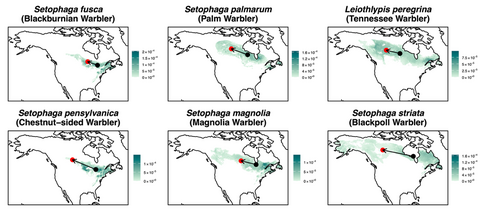

Since 1967, Southeast Farallon Island, located 30 miles west of San Francisco and a part of the Farallon Islands National Wildlife Refuge, has been an important location for Point Blue to monitor wildlife populations and study bird migration, including vagrancy. Over the course of seven years, the research team collected feathers from six species of American warblers — members of a diverse assemblage of small songbirds — occurring on the island as vagrants. For two of the species, the team also analyzed feathers from museum specimens recorded as vagrants in California between 1897 to 1996.

The researchers fed bits of the feathers into a machine to determine their hydrogen isotope ratios. Hydrogen atoms in water are typically made up of one proton, one electron, and no neutrons. But another version — or isotope — also occurs naturally. It’s called deuterium, and it does include a neutron. Deuterium is less common than standard hydrogen, but the two isotopes exist in predictable ratios in waters around the world. When birds consume food and water, the isotopic signature of their home range gets stuck in body tissues, including feathers.

By revealing the hydrogen isotope ratios in the feathers, the researchers hoped to understand exactly where in their breeding grounds the vagrants originated. This knowledge could provide a foundation for more testable hypotheses about vagrancy, migration mechanisms, range expansion, and more.

The hydrogen isotope analysis revealed that all six wood warbler species originated from the western portions of their respective breeding ranges, which were roughly located across Canada’s large boreal forest. The originating populations also happened to have fewer birds than the eastern parts of the breeding range.

“You might hypothesize that any bird has the potential to just go off in a random direction and end up anywhere else, but that’s not what we found,” Van Doren said. “Another hypothesis is that birds living in more densely populated areas are more likely to become vagrants. Our results didn’t support that idea, either.”

These results, however, do support research from Southeast Farallon Island conducted in the 1970s, when Point Blue researcher David DeSante determined that Blackpoll Warblers on the Farallon Islands were migrating to the southwest. Based on his findings, he hypothesized that these vagrants (and other more typical East Coast migrants that were arriving on the islands) had a mirror-image misorientation that was sending them to the southwest instead of the intended southeast.

The new results are consistent with this hypothesis, but the study wasn’t able to confirm whether this specific type of navigational error is fully responsible for vagrancy.

Although misorientations very rarely turn out to be beneficial, Van Doren says it’s not out of the realm of possibility. The fact that the Farallon Islands vagrants came from the western portions of their breeding ranges may allow these populations to establish a new migration route or wintering ground along the West Coast.

“With climate change, places that were previously inhospitable could now be suitable in the winter. Vagrant birds could be the start of populations adapting to changing habitats and might actually be a critical part of the cycle of range expansion in migratory birds,” Van Doren said. “You could think of these rare birds as possibly the vanguard of population change and geographic distribution change.”

Even with this new information, the researchers still do not know how birds decide to fly in new directions. For example, if one long-held theory of songbird migration is correct — that offspring inherit an internal compass direction from their parents — a simple mutation in the genetic compass could explain vagrant birds.

Van Doren plans to explore the mechanisms of vagrancy and how this process might feed into the evolutionary establishment of new migration routes. In the meantime, he’s urging other ornithologists to consider the origins of vagrants in the hopes that the field will one day settle on a unifying theory of songbird vagrancy.

“These rare bird occurrences could just be lost birds that are not going to survive,” Van Doren said. “But there is another perspective, that maybe they're not so ‘lost.’ Maybe they are explorers.”

The study, “Shared origins of six songbird species occurring as vagrants in California,” is published in Ornithology [DOI: 10.1093/ornithology/ukaf057]. Authors include Eliana Heiser, Andrew Farnsworth, James Tietz, Marshall Iliff, and Benjamin Van Doren.

Research in the College of ACES is made possible in part by Hatch funding from USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. This study was also supported by a Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) Alumni Association Student Grant, a Rawlings Cornell Presidential Research Scholarship, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Additional support came from Actions@EMBF. Funders for Point Blue’s Farallon Research Program include the Elinor Patterson Baker Trust, Bernice Barbour Foundation, Frank A. Campini Foundation, Farallon Islands Foundation, Richard Grand Foundation, Kimball Foundation, Marisla Foundation, Giles W. and Elise G. Mead Foundation, RHE Charitable Foundation, Volgenau Foundation, and individual donors.