Safeguarding soybeans: Preserving genetic diversity for a resilient future

Inside a large walk-in refrigerator on the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus, thousands of envelopes hold the fate of global food security, not to mention a significant portion of the world’s economy.

The National Soybean Germplasm Collection, maintained by a small but mighty USDA Agricultural Research Service team, is the country’s only public soybean seed bank, encompassing nearly the whole of the crop’s genetic diversity and impacting nearly every soybean product grown today — not just in the U.S., but across the world.

Each seed contains unique gene combinations breeders can mine to create new soybean varieties that can withstand emerging threats. ARS and College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences researchers are constantly digging into the collection, but they’re not the only ones. Unlike privately held collections and those housed in other countries, ARS freely distributes seeds for research purposes to more than 400 requesters each year.

With dozens of research groups mining the genetic repository each year, the collection has given rise to some of the most important soybean traits on the market.

“Most varieties grown in Illinois have resistance to soybean cyst nematode thanks to the collection,” said Brian Diers, soybean breeder and emeritus professor in the Department of Crop Sciences in ACES. “Without that resistance, it'd be hard to grow soybeans profitably.”

The collection has also enabled resistance to economically important diseases like brown stem rot and Phytophthora in the U.S. and soybean rust in Sub-Saharan Africa, without which the continent’s nascent soybean industry would likely stall out. The collection has also enabled higher protein seeds and oleic acid levels, making soybean oil healthier and more stable.

How it works

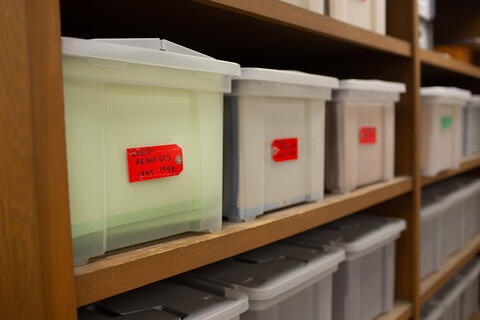

With century-old origins, the world’s only soybean seed bank comprises seeds from nearly 23,000 soybean plants and their closest relatives, harvested from all over the world. Recent facility upgrades could expand the collection to 40,000 accessions and continue its work well into the future.

Kept near and below freezing, the seeds remain viable for a decade. Every accession — seed source — must be taken out of storage every 10 years and grown to regenerate more seed for the collection. That means the highly trained ARS team grows 10% of the total collection each year; that’s 2,300 plants to meticulously mark, sow, measure, weed, harvest, dry, and store.

It’s not easy, especially for accessions representing extreme maturity groups like those adapted to cold northern climates or perennial tropical varieties unaccustomed to Urbana’s harsh winters. Some years, the ARS team sows more seeds than they harvest.

But it’s well worth the trouble.

“It's critically important to maintain this collection, because if it were lost, we would never be able to recover it,” Diers said. “Where would we get all those accessions again? We wouldn't. This priceless genetic diversity would be lost to agriculture.”

While the collection has enabled major strides in soybean development worldwide, it has also been a boon for ACES scientists who serve Illinois farmers.

While the collection grows and stores all soybean maturity groups, the majority represent maturity groups III through V — the most commonly grown soybeans in the U.S. These happen to grow optimally right here in Urbana, enabling improvement of traits important to Illinois’ 43,000 soybean farmers.

“Having that vast collection so accessible to U. of I. researchers directly benefits Illinois farmers,” said Abigail Peterson, director of agronomy for the Illinois Soybean Association. “Whether it’s a new disease or soy oleic, I think the germplasm collection is the only avenue to explore and develop new traits. It's just a huge tool in our toolbox.”

Adam Davis, head of the Department of Crop Sciences at ACES and former ARS lead scientist in Urbana, agrees.

“Supported by modern infrastructure, including a newly installed $300,000 seed vault and a robust maintenance fund from the state, the Urbana gene bank is well-positioned to continue serving as a national hub for soybean genetic conservation and innovation,” he said.

“Replicating the current cold storage facility in a new location would cost $2.5 million, not including the $3.1 million greenhouse facilities needed to grow perennial varieties. That also doesn’t include office space or personnel,” he added. “The collection’s strategic location, scientific expertise, and strong ties to major institutions like the University of Illinois and the Illinois Soybean Association make it an irreplaceable asset in the nation’s agricultural research ecosystem.”

Into the future

With the soybean industry facing ever-changing pressures, it’s more important than ever to protect and invest in Urbana’s National Soybean Germplasm Collection.

“There are always going to be instances where we will need to have access to this germplasm — the most prominent being when new diseases or insect pests occur, or when diseases that have been around a long time now start to become a more difficult challenge,” said Bob Reiter, former head of research and development in the crop sciences division at Bayer. “That's where the collection becomes very important.”

Currently, ACES researchers are mining the collection for a solution to red crown rot, an emerging disease in the Midwest, and shoring up resistance to soybean cyst nematode, which has begun to evolve around existing resistance genes.

“The idea is to create varieties that have a more complete disease resistance package, not just SCN, but other diseases,” says Eliana Monteverde Dominguez, soybean breeder and crop sciences assistant professor. “You never know what's coming. We're starting to see diseases in Illinois that weren’t here 10–20 years ago. We have to be prepared.”

With new threats constantly on the horizon, the National Soybean Germplasm Collection isn’t just a resource — it’s a promise. By keeping this genetic diversity alive and accessible, ARS and its ACES partners are helping ensure soybeans remain a reliable, resilient crop for years to come.

“I’ll be honest — I had no idea this collection existed,” said College of ACES alum and Illinois soybean farmer Brandon Laue. “But knowing now that so many of the traits we rely on trace back to it, I can’t imagine where we’d be without it. It’s an invisible foundation that’s quietly shaped the success of farms like mine for decades — and it’s just as critical to our future. With new challenges popping up every season, we’re going to need every tool we can get.”