Where’d you get that frog? Illinois study traces illicit online amphibian trade

Keeping amphibians as pets offers hobbyists an opportunity to connect with the non-human world, often increasing interest in conserving animals in the wild. But there’s a dark side to the amphibian trade, according to a recent study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

While the majority of the wildlife trade happens legally and follows proper import regulations, the internet and social media platforms have opened channels for illicit trade. This encompasses everything from domestic breeding of exotic animals to smuggling of rare or endangered species. Not following proper procedure can spread pathogens, threaten wild populations, introduce invasive species, and rob revenue streams from home countries, which are usually biodiversity-rich developing countries struggling with inequality and insufficient funds for conservation and research.

Until now, the scale of the unofficial amphibian trade was poorly known. Devin Edmonds, U. of I. herpetologist and lifelong frog collector, was curious. So, he assembled a multidisciplinary team to shine a light on the trade.

“At first, we wanted to figure out how many non-native amphibians are being bred and sold in the U.S., but quickly realized that data didn’t exist. We settled on online classified ads, so I started emailing computer science folks on campus to see if they could scrape the data from ads posted between 2004 and 2024,” said Edmonds, who worked on the project as a doctoral student in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, part of the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences at Illinois. He’s now a research affiliate at the Illinois Natural History Survey and program director at Amphibian Ark.

After many hours identifying species from photos in ads, and annotating price, date, location, and other information, the team collected nearly 8,500 listings representing 301 amphibian species from around the world.

“The real value is in the final, verified dataset,” said co-author Jane Du, a doctoral student in the Siebel School of Computing and Data Science at Illinois. “It's thanks to my co-authors’ domain knowledge that the raw listings, scraped straight from community forums, became an expert-curated dataset. I hope it can be a useful resource for other work going forward!”

They then compared this list with official import records from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Law Enforcement Management Information System (LEMIS), finding that 44 species traded online had no official paperwork and were sold at a 40% premium.

“The average is about $50 for a frog, but some of these frogs were selling for hundreds. I think the highest sale was $1,400 for one animal,” Edmonds said. “That could reflect the rarity of the animal or the seller trying to capture the profit associated with smuggling or laundering certain species that are particularly profitable.”

Some of the rare species without an import record may have arrived in official shipments with other animals. Often, importing wildlife only requires identification to the genus level. With many similar-looking species in a genus, mistaken identity isn’t uncommon. Once an importer realizes the mistake, though, they can inflate the price on the rare hitchhiker.

“Vague paperwork can become a loophole. If shipments are recorded only at the genus level, that ambiguity can be exploited to mask the true identities and origins of higher-risk or restricted species,” said study co-author Sam Sucre, founder of Natural Tanks in Panamá.

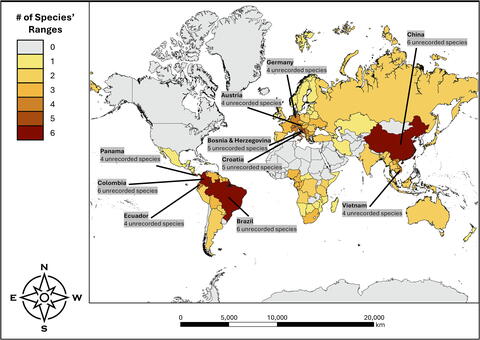

The data allowed the researchers to map the origin of most unrecorded species, revealing animals that were likely laundered: animals that were smuggled out of their home country to one with friendlier export regulations for wildlife.

“We were finding species coming out of countries with trade bans going strong for 50 years, and yet they were here in the U.S. trade. That tells us people are getting around those bans. The majority of unrecorded species in our dataset were native to Brazil, Colombia, China, and a handful of others,” said study co-author Sam Stickley, teaching assistant professor in NRES. “And the greatest number of imports at the genus level were from Madagascar, Malaysia, Tanzania, and Vietnam.”

For species that were represented in the official import records, 30 were advertised more often than expected in online sales. This suggested to the researchers that these amphibians were initially imported but are now being produced and sold domestically.

“The good news is that a lot of the amphibians being traded are captive-bred here in the U.S. rather than collected from the wild, reducing biosecurity risks and overexploitation,” Edmonds said.

In addition to providing some of the first estimates of the scale of the unofficial amphibian pet trade, the researchers have suggestions to improve sustainable trade.

“Most people keeping amphibians really care about them, so raising awareness of where they’re coming from is an important first step. We should be engaging with domestic breeders and consumers,” Edmonds said. “But it’ll also be important to update old taxonomies so that sensitive species don’t get lumped in with others in their genus, and to improve amphibian identification tools for folks inspecting wildlife shipments.”

The study, “Tracking the hidden trade of non-native pet amphibians in the United States,” is published in Biological Conservation [DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2026.111714].

Research in the College of ACES is made possible in part by Hatch funding from USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

The Illinois Natural History Survey is part of the Prairie Research Institute, and the Siebel School of Computing and Data Science is in The Grainger College of Engineering at U. of I.