Protein involved in nematode stress response identified

URBANA, Ill. – When humans experience stress, their inner turmoil may not be apparent to an outside observer. But many animals deal with stressful circumstances – overcrowded conditions, not enough food – by completely remodeling their bodies. These stress-induced forms, whether they offer a protective covering or more camouflaged coloration, can better withstand the challenge and help the animal survive until conditions improve.

Until now, it wasn’t clear what molecular trigger was pulled to allow this structural remodeling in times of stress. But researchers at the University of Illinois and the University of Pennsylvania have discovered the protein responsible in the roundworm C. elegans.

“We’re using a really simple animal system to understand basic biological questions that have implications not only for nematodes, including important crop parasites, but also for higher animals, including humans,” says Nathan Schroeder, assistant professor in the Department of Crop Sciences at U of I, and author of the new study published in Genetics.

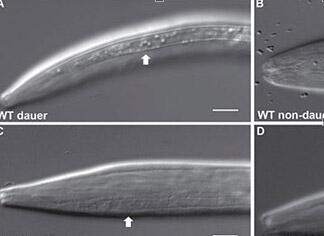

When C. elegans larvae are stressed, they stop eating, their development halts, and they enter a stress-resistant stage known as dauer. In this form, their bodies become distinctly thinner and longer and develop an outer cuticle with ridges from tip to tail.

Schroeder and his team were investigating a protein called DEX-1 for an unrelated project when they noticed worms without the protein were “dumpy” in the dauer phase: they remained relatively short and round. Intrigued, the researchers decided to characterize the protein and its function in seam cells, the cells responsible for dauer remodeling.

“When we disrupted the DEX-1 protein, the seam cells did not remodel during dauer,” Schroeder says. “Seam cells have stem cell-like properties. We usually think about stem cells as controlling cell division, but we found that these cells are actually regulating their own shape through this protein, and that has an impact on overall body shape in response to stress.”

DEX-1 is an example of an extracellular matrix protein, a type that is extruded to form the mortar between cells. These proteins exist in every multicellular organism, not only keeping cells together but also facilitating interaction between cells. Not always in a good way; it turns out many extracellular matrix proteins, including a DEX-1 analogue, are associated with human diseases, such as metastatic breast cancer.

Schroeder says his group is interested in looking more closely at metastasis in cancers due to these proteins, but as a nematologist, he gets more excited about the prospect of understanding the basic biology and genetics of nematodes themselves, particularly parasitic species that affect crops.

“For many parasitic nematodes, when they’re ready to enter the infective stage, they have a similar process. Many of the genes regulating the decision to go into or come out of that infective stage also regulate the decision to enter dauer,” he says. “This research gives us insight into their biology and how they make these developmental decisions.”

The article, “Epidermal remodeling in Caenorhabditis elegans dauers requires the nidogen domain protein DEX-1,” is published in Genetics [DOI: 10.1534/genetics.118.301557]. Authors include Kristen Flatt, Caroline Beshers, Cagla Unal, Jennifer Cohen, Meera Sundaram, and Nathan Schroeder. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.